Early in the pandemic I advised readers to zone out, take a break, and read fiction and other works of art that have stood the test of time. There’s only so much crazy we can deal with and there’s only so much mental benefits to be had from intensively monitoring a pile of political trash.

Over a long enough time frame, the madness of 2020 will fade. However awful the damage is now and however many people’s lives are ruined by asinine government policies, the world will recover. Poverty will resume its downward stroll; capitalism will provide.

Or will it?

I have degrees in history: I am at least a bit more familiar than the average person with the abject poverty that until a few generations ago was the norm for humans everywhere, and the technological improvements that have powered and propelled our societies into the wonders they are. Through disease, genocides, world wars, rebellions and revolutions, state power, civil wars and cold wars, humanity – even the darkest moments of the 20th century – we prevailed, and came out better than ever. I write for a wonderfully optimistic site called HumanProgress, dedicated to displaying misperceptions about the state of humanity. I adore the ‘New Optimists’ and their relentless work in showing us exactly how much progress we’ve made.

But I confess: this year, I’m afraid. I fear the ‘new normal’ and the ‘next normal’, and how easily we surrendered hard-earned freedoms. I fear the people who, loudly and unironically, push for states to restrict life even more, to throw everything and the kitchen sink at what looks like a bad flu season. Do we honestly think we’ll get back the freedoms that we have lost?

In ‘Can We Talk About Something Else Now?’, I gave a shout-out to the great economic historian and political economist Robert Higgs, and called his work “an eerie reminder of the long-run interplay between government and freedom”. What propelled Higgs to fame in libertarian circles was his principled, unwavering critique of state power. He didn’t mince words about the government. When I first met Dr Higgs six years ago, he struck me as a little too cynical and a little too paranoid; surely, the things he professed about the overreach of American government couldn’t happen? We’re past such monstrosities. We have checks and balances that still work – for now, anyway.

With the disaster of this year, Higgs’ words look remarkably prescient. And I’m not the only one painfully reminded of his work: Don Boudreaux and Veronique de Rugy are just two examples.

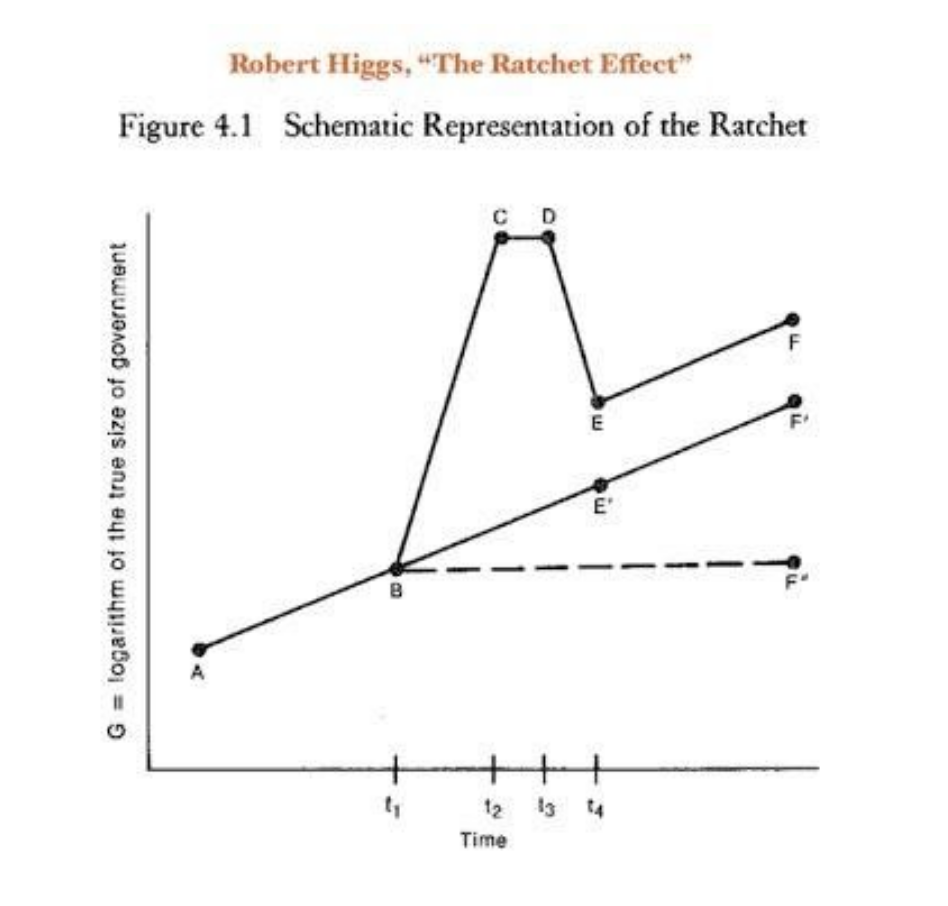

One of Higgs’ central contributions is the idea of state power ratcheting up over time. During every emergency, be it war or civil rights disputes or climate change or pandemics, the state introduces ’temporary’ one-off measures. Closing of borders, $1,200 cheques, restrictions that harm people and kill businesses – all in the need of preserving our way of life over the long run. But we know, as Milton Friedman often pointed out, that there’s “nothing more permanent than a temporary government policy”.

Ask Sweden and its recently deceased star economist Assar Lindbeck, fighting as he did his entire career against rent control – a ‘temporary’ measure introduced after World War II. Or the punitive marginal income tax on top incomes, levied as a ‘temporary’ public finance effort during the banking crisis of the 1990s. Even after public finances had been under control and in good shape for at least twenty years, the worst portion of this expropriation was rolled back only this year – sending Sweden to a meagre third place in the league of highest marginal tax rates. James Buchanan predicted as much in Public Finance in Democratic Process from 1967.

How much will state power ratchet up?

Let me engage in some speculation, hopefully entirely off and ridiculed in three to six months.

Part of Higgs’ ratchet is that after the immediate emergency passes, the state surrenders some of its extended powers – but not all of them. Like the examples of Sweden’s rent control and top marginal tax, some of them linger for decades. The rest of us grow used to them, and forget that we could ever live without them.

As winter rolls over the northern hemisphere, the corona cases will increase – relatively slowly for now, then faster and faster. Death rates might move up with it, and everyone will freak out. Most governments are already losing their minds, reintroducing heavy restrictions on what its ‘free’ people may or may not do. They cover this in increasingly Orwellian euphemisms (‘circuit breaker’ sounds technocratic and harmless, right?). Some, like the editorial writers at The Guardian, don’t even pretend any longer:

“The most obvious advantage of one rule for everyone is its simplicity. Arguably, the sense of being ‘in it together’ from March onwards also made a positive difference in terms of people’s sense of wellbeing, their willingness to tolerate hardship and offer help and appreciation to others.”

It’s not about what works and what doesn’t, a disease or how best to combat it. It’s not even about weighing one set of ills against another. It’s about feeling good and about being in it together – suppressing everyone’s rights and freedoms together.

We thought they’d never infringe on people’s freedom to walk outside, meet others, trade in perfectly harmless and mutually beneficial exchange. We were wrong

Air travel won’t return to its 2019 peak. Fewer people will fly, eschewing the wonders of Elsewhere for the safety of Somewhere. The prospects of mandatory quarantines, sometimes in both directions of travel, will sway all but the most dedicated people from travelling. Those who venture into these remarkably safe wonders of civilisation will find themselves going through an additional ordeal – not unlike what happened after 9/11 (another set of freedoms never returned to us). We’ll be wearing masks for many years to come, possibly forever; food and drinks will not be served; hand sanitisers and wipers ensure that nothing ever touches your skin. The slight silver lining is some extra space as under no circumstances will seat neighbours be permitted – which means that airlines will struggle with profitability, see more future bailouts, and some of them probably nationalised.

The comparatively harmless plexiglass will be everywhere, as will the masks that make it impossible to read others’ facial expressions and on occasion hear what they’re saying. Social interaction will be inhibited, and not just physically. We’ll all make our purchases behind protective veils – or through the pseudo-anonymity of being online – losing the affectionate interactions that make market participants friendlier. Say goodbye to late-night rumblings through the streets – nightclubs and bars will stay closed, permanently, as such frivolity is most certainly not ‘essential’. If you’re even allowed outside, that is – which you won’t be – there will be few reasons for you to leave the safety of your home.

Vaccines will arrive, faster than ever before in human history, but the combination of not providing enough protection and a sizable portion of the population refusing to take them, will mean that corona restrictions remain in place.

The madness of 2020 has had a lot of extraordinary firsts: lines in the sand we never thought politicians would cross. We thought they’d never infringe on people’s freedom to walk outside, meet others, trade in perfectly harmless and mutually beneficial exchange. We were wrong: at the first sight of (slight) danger, we handed over freedoms left and right – and nobody really cared. Higgs’ thirty-year-old words are more relevant than ever.

When even free-marketeers like Tyler Cowen say that opening schools “just doesn’t seem worth it”, we don’t want to know what he thinks about other activities. In the early days of the pandemic, opponents of freedom said smugly that: “There are no libertarians in a pandemic.” Perhaps, we reluctantly conceded as we all feared what we didn’t know, before we retorted that there would be no statists coming out of one. Liberty’s proponents seem to be losing that one too.

“The benefits of a national lockdown no longer justify the costs,” states The Economist, as if they ever did or as if that mattered to power-hungry intellectuals and politicians. The latter have been enjoying a seven-month high on dominating others – and learned that their subjects didn’t really mind. They will fight tooth and nail to hold on to their newly acquired powers, and there will be nobody opposing them.

What Higgs teaches us is that temporary efforts, introduced for whatever high-flying reason, take on a life of their own. They lull the population into a false sense of security and a misplaced appreciation for the now normal. Fast forward ten or twenty years and everyone forgets that the invasive powers we transferred to the state were ever temporary in the first place. Higgs is the intellectual champion we don’t deserve, but so desperately need.

Let’s just hope that I am wrong, and that progress wins out in the end.

This article was originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research.