Originally published November 2021.

It has been said and written with such earnest despair to have become practically axiomatic: 22 will prove a year of acute pressure on household finances across the UK, the first year of what could prove many.

This narrative invariably includes the warning that the UK faces years of tensions between its Parliament and that of the EU, as well as within Westminster itself; not merely across benches, but internecine. Quite frankly, one risks not merely being considered a heretic to play down matters, but accused of economic and political illiteracy. After all, how can 22 not be an annus horribilis for the UK economy when energy bills and costs more generally are spiking, taxes are hiking, the base rate rising and so many in the labour force isolating? A torrid year in prospect too since many Brexit issues remain extant, while the seeds of secession are still being sown in Scotland and the PM faces dissent in his own dissatisfied ranks.

That there are a raft of factors that will press home negatively on household finances and general sentiment is not in doubt. The reality, however, is these are only part of the collective picture for the UK economy and its households in 22 and the years that follow, for there is no shortage of positives.

There is, for instance, the considerable hoarding of aggregate savings enforced on UK households over the past two sedentary furloughed years – a quarter of a trillion pounds according to the ONS –I will not even try to estimate the windfalls purloined from all the generous State-funded schemes announced by the Chancellor.

We must also add in the fact that home owners have enjoyed two years of appreciating asset wealth; residential values up on average by one-sixth, producing in aggregate a wealth boost of circa £1tr, a staggering addition to the positive equity in homes built up since 08, from when mortgage rates fell sharply in line with the base rate. And, while the amassing of cash and housing equity wealth represent strong positive entries on balance sheets rather than cash flows, the former can easily be transferred to the latter through equity withdrawal and moves from savings to current accounts. Whatever way strongly enhanced household wealth is converted into consumer spending, it’s worth keeping in mind this comes with what could easily be a multiplier of 20 times (viz a 5% saving ratio).

“far from a small number of UK households and firms have, in fact, worked and earned well throughout this crisis”

There is another economic positive from this accursed virus which will deliver an economic shot in the UK arm that many in polite society will consider highly insensitive in my raising. Insensitive, that is, because it has involved UK households capitalising – perfectly legally capitalising, that is – on the medical crisis we have suffered. Specifically, far from a small number of UK households and firms have, in fact, worked and earned well throughout this crisis. They have done so because, though parts of the economy have been closed off, others have not merely kept open, but have been working and earning overtime like never before. The coronavirus crisis has left many households sitting financially more comfortable than they could ever have estimated two years ago. To be clear, highlighting that striking variations exist in no way denies the fact that many have suffered dire monetary pressures because of the crisis.

What then of borrowing costs? Well, here we will be dealing with comparatively small moves in the base rate from an ultra-low level – we expect it to rise to at least circa 1.5% over the next two years. These moves will moreover happen in an extremely competitive UK marketplace for home loans and indeed debt more widely. As such, we could well see mortgage and credit rates holding steady if not falling. The arrival of fintech disruptors is indeed merely one part of ongoing disruption in the UK that moderates our cost of living and actually lowers it in more than a few cases; early disruptors, being disrupted in turn, with this process ongoing.

I turn now to what many see as ‘the elephant’ in the UK ‘room’ which will leave the UK economy with very little space for growth: the monetary pile of state debt accrued over close to two years of frenetic exchequer funding. In addressing the mammoth UK state debt amassed since March 20, we need to remember that the money created has not vanished. It has not vanished because, for the most part, it has been a monumental fiscal transfer. Indeed, much of the wealth windfalls identified above as large positives incubating within the UK economy have accrued because of this large negative appearing on the UK’s exchequer ledger. The debt has, in short, been a balance sheet transfer. As for who will ultimately come to make good on the Exchequer’s viral liability, the answer is the UK taxpayer in part and most likely, in even larger part, overseas investors. We must, after all, bear in mind how sterling is growing anew in terms of its global importance as an official foreign currency reserve. Indeed, the pound has a circa 3% weight in China’s FX Trade System (CFETS) basket – a remarkable figure given it had no official weight as recently as December 2015. Indeed, the pound’s weight in China’s reserves is not only likely to edge higher, but become a beacon for a far broader international appetite for UK debt. This increased consumption of UK gilts will contribute to containing their yields – and for sterling-denominated debt more generally – and moreover act to lift sterling itself.

As for UK tax payers and their part of ‘the tab’ built up by the Chancellor since March 2020, we will indeed pay up. We will, however, largely do so through the upward fiscal drift that comes with economic growth. For instance, as employment levels and incomes rise, as they both most certainly will, many more will fall into paying tax, with many others moving up into higher tax brackets. Moreover, as we spend the wealth windfalls noted earlier, more sales tax receipts will accrue to the Exchequer. This is not fanciful arithmetic, but how pro-cyclical ‘tax capture’ works in a well-working economy.

Let me next address those who draw parallels between the financial crisis of 2008 and the medical one of late. Those, that is, who point alarmingly to the austere years which followed then and warn of the same from now. For my part, I see little real equivalence between then and now. Back then many UK banks were largely ‘broke’, whereas now the entire sector is very much well balance-sheeted and very much looking forward to interest rates moving – gently – upward. Also, while back in 2008 the UK property market was in very poor shape, it is now in very much good health and is building on this. Back then, China’s appetite for all things British was in its infancy, whereas now it is very much grown-up, with an appetite of heathy adult proportions. To those who point out how China features strongly in my outlook for the UK, I say, well spotted.

It is worth noting that given its extremely well developed and world-leading ecommerce sector (with over 30% of retail sales taking place online), the UK economy has been able to more effectively capture the spending of those locked-down like few, if any, other nations. Indeed, the enforced uplift in our use of delivery ‘goods into our hand’ has meant a great deal more hands being employed – resulting in a permanent boost to the labour market, which brings us to hiring.

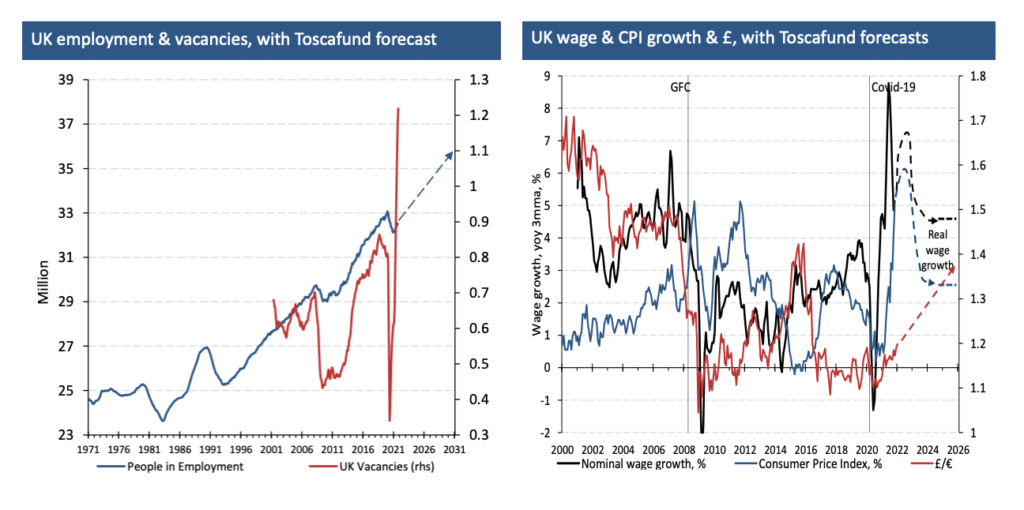

In considering UK household fortunes in 2022, one need allow for the evidence of exceptionally strong hiring intentions – as seen in record-breaking vacancy data. This is something certain to lift average wage levels; 7% inflation, which is my estimation for the peak to reach. The far from unwelcome bidding up of ‘wages’ will prove a permanent income uplift and of course a monetary benefit to household finances through a year of sharply elevated energy costs, such that CPI growth could reach 6%. Reach, indeed possibly breach, 6%, yes, but it has to be added, very quickly retreat below 3% thanks in part to the competitive consumer marketplace the UK now enjoys. Remember, too, that a degree of inflation should be welcomed in any healthy economy, the far more feared virus being deflation. For the record, I expect UK wage growth to settle at an annual rate of circa 4.5% out to 2026. Furthermore, a strengthening sterling will act as a disinflator, easing both CPI and wage growth.

Another certain addition to the UK household collective in 2022 will be the return of many hundreds of thousands of EU nationals with settlement status and others having successfully sought visas. Part of the reason for this will be the evident strength in demand for labour within the UK and the prospect of earning in an ever-stronger sterling. Controversial as it is talking up the pound, it is one I will confidently make all the same. The pound will be lifted in tandem with BoE’s firm policy action and the ECB’s lack of it. Sterling’s looming strength is something which will also help raise purchasing power for all UK households. As for where GBP will end the year against the euro, my conservative estimate is at least 10% higher.

Now, while it might seem premature when self-isolation remains rife, to claim the disruption this is causing the UK economy will soon effectively end, it will end and very soon. And, as we return to work, more quickly than elsewhere across Europe, the draw of working here will be all the greater. This leads, of course, to what seems the interminable debate over Brexit.

The point I would make concerning Brexit and the endless debating on ‘Final-Final’ terms is that this has not been in any seeming material way a brake on the economy of the UK writ large. The issue of the UK writ large leads, of course, onto the very much distinct medical management through this viral crisis and the prospect this is a precursor not to ‘Sexit’ but a widespread separation of powers within it, including fiscal devolution.

When fiscal devolution finally comes to the UK, it will propel all the more an entirely new economic growth dynamic within it; the heat-map of which I am convinced we will start to see being colourised in earnest this year. Witness, that is, strong economic growth across large tracts of Central and Northern England (CaNE). With this in mind, let me present our ‘Regional growth fuature-ometer’, which highlights where, over the next five or so years, the UK’s economic ‘hottest spots’ will be.

It is a composite of 27 wide-ranging measures capturing differences in regional demographics, housing, labour markets and a raft of other dimensions which, blended together, give striking colour to the UK’s economic future. CaNE will be enabled because it is well positioned. Well positioned literally, in relation to topography, and well positioned figuratively, in terms of having an existing built-presence in such markets to capitalise on an ongoing upswing in logistics, bioscience, warehousing and wider industrial growth. Wider industrial growth, that is, coming from a surge in green automotive and aerospace-making, as well as efforts to re-shore production to ensure supply security and shorten supply chains to improve E&S scores. Well positioned, too, to exploit the strong demand from high fee-paying students from the emerging world. CaNE will also be favoured because its housing markets are comparatively affordable and accessible, and so too its workforce.

On the thorny issue of UK politics, I will merely say this: an economy that managed through the political turmoil that raged from the summer of 2017 through to the end of 2019, during which there was chaos in Parliament and literally no meaningful Government, to scale to record highs in employment and hiring, need not fear whatever politics throws at it in the years ahead. Having looked at the UK economy in red and blue shades, what of the green? What of the UK economy and net carbon-neutral ambitions?

Well, while going green comes at a cost, this does not necessarily mean going deep into the red in the process. The reality for the UK economy is that reshoring production to shorten supply lines, and so lower carbon footprints, is an economic positive. An economic positive, too, arising from surging UK-based production of more enviro-friendly cars and aero-engines. One can add that ‘greening out’ our homes and places of work does not happen without labour being employed and products made. So, while economists have been as side lined in environmental strategy as they have in the management of this medical crisis, those well versed in the subject will accept that economies with comparatively low frictions to allocating capital – labour and financial – will do well. Do well too national economies with the minimal mismatch between its labour force seeking work and the work available. And do well also nations with few obstructions to the redeployment of labour and property from old markets to new strong-growth ones. I am confident that the UK is just such an economy, one which is now sufficiently supply-side reformed to quickly and successfully adapt to new environments.