Income returns are remarkably steady and predictable, and forecasts of rental growth are often reasonably accurate as they are founded in the physical world of supply and demand.

By contrast, the most challenging component of returns to predict in real estate is the yield. They are a measure of sentiment – and partly relative sentiment at that, given that real estate as an asset class does not exist in a vacuum. Real estate yields tend to be denoted as demanding a premium over the risk-free rate, typically government bonds. This isn’t the only driver of real estate yields, but it is perhaps the most important one – particularly when allocating between asset classes and estimating required returns for real estate.

In this article I examine the accuracy (or lack thereof) of bond yield forecasts, and discuss whether predicting real estate yields is, as a result, fighting a losing battle.

“What’s the harm in bringing back a little info on the future?”, Back to the Future II

I’ve referred to the LIBOR/SONIA forward curve ‘hairy chart’ in a previous blogpost (see The Emperor’s New Real Estate: Seeing what you want to see). The financial markets are not particularly adept at predicting the trajectory of bond yields. That’s not a criticism; why should they have any particular insight? In fact, we should really think about the forward curve as a sentiment indicator rather than a forecast or, more accurately, an implied forecast.

Therefore, for this analysis I will instead consider econometric forecasts of bond yields. Their modellers will surely be taking note of what the market is implying, but they have the opportunity to overwrite them.

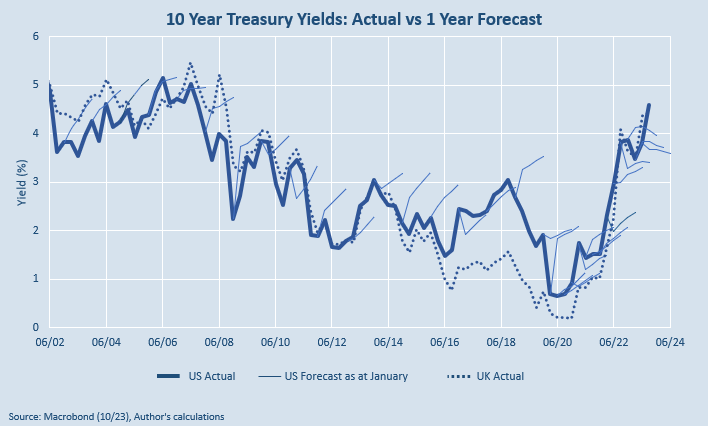

The most reputable and long-standing source of data that I’m aware of is the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters. We can see from the chart below that the econometric forecasts for US 10 year treasury yields a year in advance were poor, demonstrating very much the same biases as the bond market implied forecasts.

- Since 2002, the forecasts tended to overestimate the actual result 70% of the time.

- This ranged from 67% of the time up to two quarters in advance, rising to 75% four quarters in advance.

- This neatly showcases how time adds to uncertainty or error in forecasts, and supports an approach to prediction which eschews a a single scenario in favour of multiple scenarios.

- Many of the 30% of occasions that the bond yield forecasts undershot the outcome have come since the Covid-19 pandemic and the rapid rise in inflation.

- If we exclude these, the proportion of overestimations between 2000 and 2020 was actually even higher, at 79%.

“Anything you can do, I can do better”, Annie, Get Your Gun

Let us now consider real estate. An extremely common approach to yield forecasting and fair value analysis is to assume a real estate yield premium over the risk-free rate. Given the inaccuracy of projecting forward the risk-free rate as shown above, this approach may simply compound the errors of the former. Or, at the very least, make the model output highly sensitive to its key input.

But perhaps real estate yield forecasts are accurate in spite of the flawed risk-free rate component of the model? It could be that real estate modellers are adept at compensating for the untrustworthy bond yield element. We should give them the benefit of the doubt until we have explored the accuracy of these real estate forecasts in their own right.

I could have simply reproduced a literature review at this point, as there have already been several studies into the accuracy of real estate forecasts. But it’s always more fun to investigate oneself, is it not?

And yet, assessing the accuracy of real estate yield forecasts in a comparative way is tricky. The best source of data I am aware of is the IPF’s quarterly consensus forecasts, dating back to 2005, which is unfortunate in that it doesn’t actually contain any yield forecasts! What I am able to do, however, is to infer them from the total return, capital value growth and rental value growth forecasts.

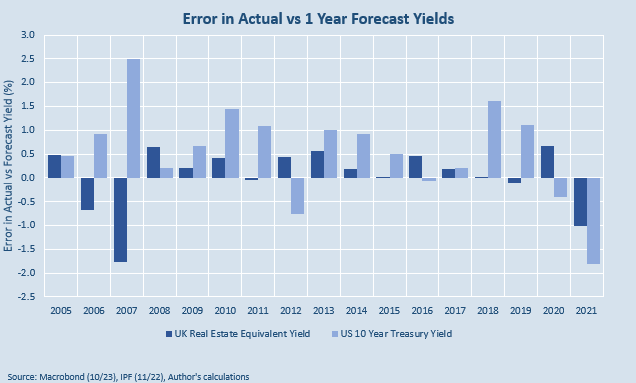

The following chart shows the error in one-year-ahead forecasts for both UK real estate yields and US treasury yields. Ideally, of course, we’d be comparing the US with the US or the UK with the UK, but I sadly do not have access to the requisite data. However, since 2000, US and UK bond yields have tracked each other with a very high correlation of 0.93 and a marginal difference of -0.13 pps. The only meaningful divergence was during the UK’s post EU-referendum phase in 2016-19. As such, we can imagine that same forecasts for UK bond yields would have been reasonably close to those for the US. As we are looking at generalities rather than specifics here, we can live with this approximation.

And so to the results. Neither set of forecasts cover itself with glory. It appears as if real estate yield forecasts are more accurate on the whole. However, that doesn’t take into account the greater volatility in bond yields, exhibiting a min-to-max range of 450 bps over this period compared to real estate’s 315 bps. It also doesn’t consider that there is a natural floor to the level of real estate yields, i.e. the bond yield itself, given it’s alternative role as the risk-free rate. Overall, in terms of forecasting accuracy, I’d say there is probably little to choose between predictions of bond yields and predictions of real estate yields.

Unsurprisingly, the two series tended to be wrong in the same direction at the same time. One exception to this is just prior to the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007, when bond yield forecasts did not anticipate that yields would fall whilst real estate commentators did not predict property yields would rise – in my mind, the former is the more forgivable oversight. This was the one and only time since 2005 that the two series moved meaningfully in opposite directions. They were both wrong, but for different (albeit ultimately related) reasons.

“Little drops of water make the mighty ocean”, Julia Carney

In one sense, that the real estate yields were only as poor as the bond yield forecasts, as opposed to orders of magnitude worse, could be seen as a win.

And, as most of the errors in equivalent yield forecasts on the chart look quite modest, you may ask whether we even have a problem here at all. Alas, we do; even a small shift in yields translates into a much larger impact on total returns. For example, the average annual positive error during the low-error years of 2008 and 2020 was +35 bps. This would have resulted in a not-so-modest annual negative yield impact of -5.3% on the average equivalent yield over the same period.

We learn from this that, if your strategy relies on accuracy in your projections, you can’t afford to miss. However, the likelihood is that you will miss.

“It’s okay to make mistakes. Mistakes are our teachers, they help us to learn”, John Bradshaw

As long as investors are aware of the challenges in predicting both bond yields and real estate yields – even just one year ahead – then I have no argument should they wish to use them. It would make sense, however, for them to considerably reduce their level of confidence in them, particularly as the time horizon extends, and plan for more than one version of the future.

This article was originally published in My R.E. Education and is republished here with permission.