Chancellor Sunak will need a Plan B.

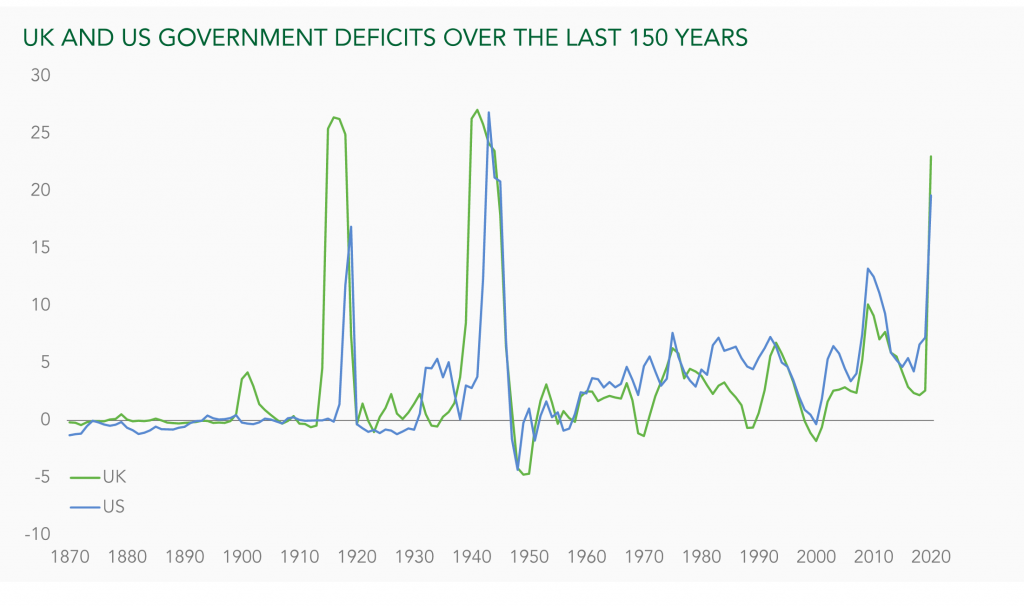

The coronavirus pandemic has hit public finances like a war. Across the world governments have scrambled to offset the economic and social impact of the virus. Huge, and necessary, rises in public spending have pushed government deficits to levels not seen since the two world wars of the 20th century.

The numbers are enormous: UK government debt now tops £2trn1 whilst the US owes an eyewatering $26trn.2 The picture is similar across Europe, with many other countries also seeing debt/GDP ratios rising to over 100%.3

At Ruffer, we think such debt levels are simply too big to be repaid through tax rises. In the UK, increasing everyone’s income tax by 1% would only raise an estimated £5bn-£6bn.4 Similarly, a 1% rise in VAT would raise about £7bn.5 Neither of these would make any noticeable dent in this mountain of debt; even doing both would still take 150 years to pay down today’s debts. No wonder Rishi Sunak cancelled his autumn budget – he’s going to need a Plan B.

Fortunately, zero interest rates mean there is no immediate need to repay the debt. But eventually it will need to be tackled. If raising tax won’t do the job, how can governments get deficits down to manageable levels?

It looks like inflation, not growth, austerity or taxation, will have to do the heavy lifting

Perhaps history can help us. After the First World War, Britain opted for austerity and government spending fell by 75%.6 Unemployment soared and the country suffered a deep depression. The medicine worked, but it almost killed the patient. This is simply politically unacceptable in today’s world.

The Second World War may hold more clues for today’s policy makers. A combination of rapid post-war economic growth plus a healthy dose of inflation saw deficits fall rapidly. In the 30 years immediately after WWII nominal growth averaged 8.8% – made up of 2.3% real GDP growth and 6.5% inflation.7

This time, however, such levels of economic growth are likely to be harder to achieve. There is no post-war rebuilding boom to come, no peace ‘dividend’. Instead it looks like inflation, not growth, austerity or taxation, will have to do the heavy lifting.

That said, taxes may well still rise. The chancellor may have higher rate income tax in his sights, or capital gains, or even a wealth tax, but this will be for political reasons and will likely be limited in impact.

So, could it be that inflation, not tax, poses the greatest risk to savers today? Perhaps this will turn out to be Rishi Sunak’s Plan B. At Ruffer we think history shows that this is a risk worth protecting against, so over 40% of our portfolios consist of inflation-linked bonds and gold. After all, as Ben Bernanke told the National Economists Club back in November 2002: “government has a technology, called a printing press…”.

Footnotes:

- Office for National Statistics, Public Sector Finances UK July 2020

- US Treasury, Debt to the Penny, 30 September 2020 Fiscal Data

- Goldman Sachs, 24 March 2020

- Institute for Fiscal Studies, September 2020

- Ibid

- The National Archives

- OBR Office for Budget Responsibility, Post-WWII debt reduction, 11 September 2017

Past performance is not a guide to future performance, investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. The information contained in this document does not constitute investment advice or research and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision. References to specific securities are included for the purpose of illustration only, they are not a recommendation to buy or sell.

This article was previously published by Ruffer.