Originally published May 2023.

Of the great many motives for one ‘labouring a point’, despite a backdrop of derision and dismissal, most are far from great. Of these, the most disagreeable is an unyielding stubbornness even when reasoning is churlish and, in the face of evidence, the assertion is plainly wrong. To be clear, my persistence is not founded merely on a strong fundamental conviction, but when I am convinced the shock — which I see blindsiding the consensus — threatens to be so costly, it will be felt by us all.

With the above in mind, let me repeat that such have been the economic stresses hitting the likes of Poland, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova, one will soon succumb to a devaluation which triggers the others to follow. I claim that the currencies of these nations are poised to weaken noticeably with the same conviction I held that the Turkish lira and Egyptian pound would do so. And devalue they have; with, be in no doubt, further lurches lower to come.

As to why I am so strident in making the dramatic claims above, the answer comes in two parts. The first is the backdrop of the sizeable real and monetary shocks which have struck those EU ex-eurozone economies, in the direct environs of what has unfolded in Ukraine. The second reason is the stubbornness with which the ECB is pushing ahead with a hawkish monetary stance. Pushing ahead, that is, with little or no consideration for the collateral consequences; i.e. the impact on the currencies of these nations governed by Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) II strictures that do not countenance their central banks ignoring how the ECB acts. Just as we witnessed Erdogan make his central bank sacrifice the lira rather than defend it with ever more elevated interest rates, I expect ‘the unilateralist’ Orban to follow suit. If the forint devalues, the Polish zloty and Romanian leu will not be that far behind. If Romania’s leu devalues, how on earth could Moldova’s leu hold firm? How too could Serbia’s dinar hold up, and Bosnia’s convertible marka? What then of the Albanian lek — even with its exceptional remittance support, could it withstand region-wide devaluations? Well, the idea these would somehow hold-up, could not hold up to any sensible scrutiny. And once devaluations do hit, inflation will surge anew.

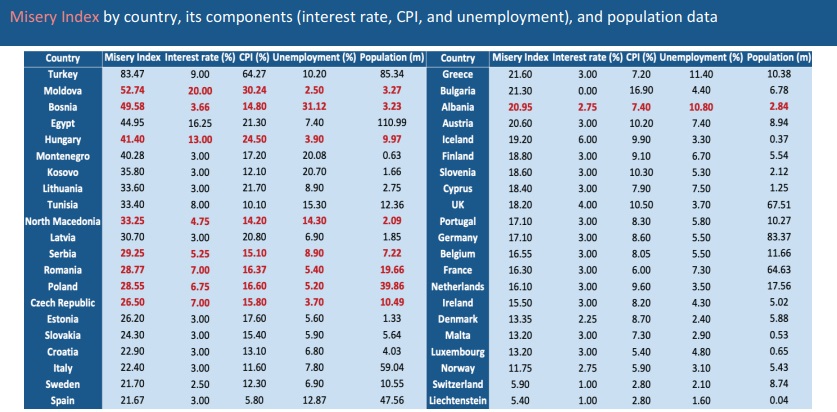

Along with his eponymous law, Arthur Okun introduced into economic empiricism the ‘Misery Index’ (see Table). Okun believed that adding the rates of inflation and unemployment of an economy provided a convenient, accurate and plausible gauge of the degree of misery experienced by its population. In 1999, Robert Barro augmented the Okun version to create his own, the BMI, where the interest rate was added and so too the shortfall of GDP growth from trend. Whilst a useful metric, ‘Misery Indices’ break down when there is considerable movement of labour respectively out and into the economy in question. Consider the rather modest ‘Misery Index’ being recorded by Albania. Given the seemingly unrelenting sizeable emigration of its prime agers, Albania’s unemployment rate can hardly fail to be subdued. Moreover, the remittances from its large expatriate population acts to support, indeed lift, Albania’s lek, and as such, moderate inflation and suppress the interest rate. What then is macroeconomically unfavourable prime-age depopulation, paradoxically produces what appears to be favourably low ‘Misery Indices’.

It is worth briefly considering here the tussle between Europe’s single currency and that of the USA. If the euro soon resumes its strength against the dollar, this will be come with serious consequences for economies within the eurozone — best described as a form of winner’s curse. With the euro moving higher against the dollar, and the latter continuing to appreciate against the Turkish lira and Egyptian pound, the euro will move all the more against these. As it does, the EU currencies which are supposed to dutifully follow the euro, will find their effort as such to be ever more monetarily painful. For not only will their central banks be expected to raise interest rates in some degree of synch to an avowedly hawkish ECB, but they will also find the ascent in their currencies to be another avenue of monetary tightening.

One European currency thus far unmentioned is the unloved pound; representing the economy the IMF has deigned to be the worst performer of this year. But since the IMF fails to see the adverse shocks set to hit continental Europe, we can hardly trust its outlook for the UK. If and when the devaluations forecast in this piece come to pass, sterling cannot fail to respond with a lurch higher, and so too will efforts of a great many across the continent to enter the UK for work. Other currencies unmentioned include the yen, the yuan, or for that matter, many others. I have chosen not to dwell on them not because of their unimportance. The issue is that Tokyo raising Japan’s defence spending by redeeming their Treasury “savings” reinforces the conclusions outlined in this piece. So does, in fact, Beijing pursing ever greater renminbi internationalisation and as such, diminishing the dollar’s long-term and thus far stubborn hegemonic hold over global transactions and international savings. The simple fact is that general dollar weakness has to involve it rising against the euro, thus exacerbating the forces which I have suggested will act to ignite devaluations within ERM II against the euro.

Many will of course also be familiar with its predecessor to ERM II, ERM I, and be aware it was how over a dozen EU currencies were marshalled first into the soft ECU; then on January 1st, 1999, the soft euro; and forged into the physical version three years later. Recollections of the success of ERM often miss how the European Monetary System, which formed its command-and control centre, was seriously shocked a decade before the hard euro was formed.

The constellation determined by ERM II has become untenable. There will of course be those claiming this is all hyperbolic and sensationalised. To these, all I will say is that when the shocks of September 1992 hit, very few were expecting them, albeit a great many have since claimed, most disingenuously, they not only did but profited as such. Well, let’s see what profit lies (sic) ahead.

When I read how sanguine the ECB happens to be concerning the economic future of its jurisdiction, and see almost no meaningful critique of this, I ask myself, am I missing something obvious, or are they?